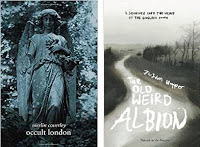

Justin Hopper. The Old Weird Albion. Penned in the Margins, 2017

These are two quite different books, but linked by one theme, the magic, legend and memory of place. Coverley’s book is ostensibly a straightforward guide-book to London, pointing out locations associated with various figures and ideas associated with the history of occultism and magic, from John Dee’s Mortlake (and I’ll have something to say about that later) to Highgate and territories beyond Zone 6.

🔽

Hopper’s book is more personal, searching for memories of a relative he never knew, amongst lost and liminal places along the South Downs.

To many people the streets of London seem hard and materialistic, a litany of banks and estate agents, faceless offices, security barriers, building sites and traffic fumes. Unlike the South Downs, a protected National Park, winding on a chalk spine from Winchester to the coast at Eastbourne. Here the magic is more overt, and Hopper describes his encounters, as he walks this path, where the skin of modernity is sometimes stretched thinly over an older land.

Hopper’s grandfather’s first wife, Doris, one day in 1932 walked over the cliff at Beachy Head, at the easternmost end of Hopper’s walk. As he progresses towards this spot he uncovers clues, from the landscape, from the people he meets and from family memories, that reveal, but never quite explain, her story. On his walk he meets musicians, magicians, crop-circle makers, archaeologists, wanderers and suicide vigilantes. He wanders through villages which have disappeared with virtually no trace – far more lost than Wiltshire’s lost village of Imber.

There are lost pasts, but he also encounters lost futures, the Utopian-seeming plan for the township of Peacehaven, intended as a beacon for the world that was to arrive after the War to End Wars, now a gently mouldering footnote to the English suburban dream, but still capable of holding at least one disturbing memory.

There are odd cameos here, the saxophonist vamping in a lonely country church, the ley hunter tracking a path through rain-soaked coppices and over crumbling walls; and morris dancers appearing through the morning mist at Chanctonbury, then disappearing with just the sound of their bells fading into the distance.

Hopper eventually comes to some sort of ‘closure’ to Doris’s story, which curiously ends in Essex rather than Beachy Head, a place synonymous with suicide in the English collective unconscious.

Occult London is a straightforward history and guidebook to London locations and the individuals from the history of magic and the occult associated with them, from the era of John Dee to modern occultism and psycho-geography. And here I must point out yet again that the library of the great Doctor Dee was not ransacked by the ignorant residents of my adoptive town of Mortlake in some Simpsons-style orgy of pitchforks and burning torches. On the contrary, Mortlegians regarded him with a great deal of respect – although a little warily, that long white beard was a bit off-putting – asking him to adjudicate in local disputes. In reality his library was dispersed through the neglect and carelessness of his brother-in-law Nicolas Fromonde who freely ‘lent’ his books to all and sundry while the Doctor was travelling abroad.

That off my chest, I will say that they rest of the book is a neat summary of the occult life of London, with all the usual suspects noted, and linked to premises in the capital where they lived, died, outraged the neighbours and otherwise operated.

The second half of the book is a gazetteer of London districts associated with particular individuals and movements. It reminds us that certain places contain their own genius loci, maintaining it over centuries - revolutionary Clerkenwell, radical Lambeth, louche Soho – as well as areas that change and morph into new identities.

I’m not sure whether ‘psycho-geography’ has any real meaning, other than a ability to absorb the atmosphere of an area and an urge to understand not just its history but how that history influences its present and its people and its entire structure, and what still surrounds us as we walk its streets, lanes and fields. Both these books help us to see something of that atmosphere

But I need to know more about the Nuns’ World Snooker Championship held at Tyburn Convent in 1989 – or did I somehow wander into an un-broadcast episode of Father Ted?

- John Rimmer.

No comments:

Post a Comment