Richard L. T. Orth. Folk Religion of the Pennsylvania Dutch: Witchcraft, Faith Healing and Related Practices. McFarland, 2018.

Richard L. T. Orth. Folk Religion of the Pennsylvania Dutch: Witchcraft, Faith Healing and Related Practices. McFarland, 2018.Books on witchcraft frequently refer in passing to the ‘Powwowing’ of the Pennsylvania Dutch, but the reader is seldom told anything about it. The present study is by a folklorist who was brought up in that culture, so he knows the subject from both inside and out.

🔽

It is evidently a combination of folk beliefs going back to prehistoric times, together with material published in German about two hundred years ago.

The traditional view, almost everywhere, posits the existence of black witches and white witches, though these actual terms have not been used very often. If a child falls ill, if a cow gives bloody milk or none at all, this is presumed to be due to a curse laid by a ‘black witch’. There are various cures available, but often the sufferer will go to a ‘white witch’, who may be termed a wise woman, a cunning man, a witch doctor, or, among the Pennsylvania Dutch, a hex doctor. “The art of white magic in the Dutch Country is referred to as 'Braucherei' or, more popularly, Powwowing.” No doubt much of this is due to paranoia, but clearly, in a society where everyone believes in cursing, some people will try to do it, a point historians often overlook.

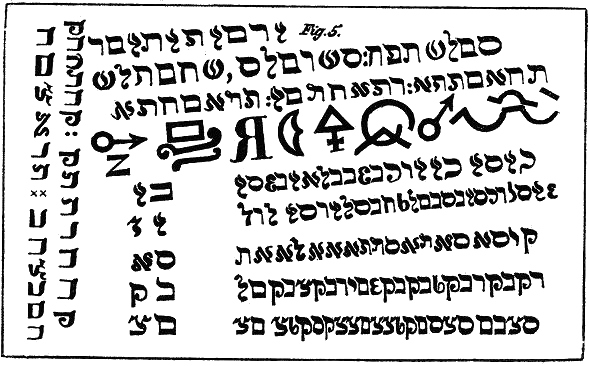

Unlike in previous centuries, there are printed texts available for both cursers and blessers. Now, the ‘Dutch’ are mostly descended from immigrants who spoke a dialect of German. Among the books that they brought with them from the old country was one known as The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses. This was reprinted in the New World and eventually translated into English. It is generally believed to have been written by the Devil, and anyone who inadvertently reads a passage must immediately read it again backwards, or risk damnation. Personally, I think this unnecessary: on examination, it proves to consist primarily of illustrations of talismans inscribed with what must have originally been Hebrew characters, but are too corrupted to make out; the instructions beneath each include invocations, written in Roman character, but evidently from a Hebrew archetype ruined by successive miscopyings. It must have been the work, in the first instance, of a pious if slightly unorthodox Jew, though expanded by later authors, mostly Christians. The title shows that it was meant to be a secret instruction of God, given after the public ones for the use of a select few only.

Unlike in previous centuries, there are printed texts available for both cursers and blessers. Now, the ‘Dutch’ are mostly descended from immigrants who spoke a dialect of German. Among the books that they brought with them from the old country was one known as The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses. This was reprinted in the New World and eventually translated into English. It is generally believed to have been written by the Devil, and anyone who inadvertently reads a passage must immediately read it again backwards, or risk damnation. Personally, I think this unnecessary: on examination, it proves to consist primarily of illustrations of talismans inscribed with what must have originally been Hebrew characters, but are too corrupted to make out; the instructions beneath each include invocations, written in Roman character, but evidently from a Hebrew archetype ruined by successive miscopyings. It must have been the work, in the first instance, of a pious if slightly unorthodox Jew, though expanded by later authors, mostly Christians. The title shows that it was meant to be a secret instruction of God, given after the public ones for the use of a select few only. For the faith healers there was Der lange Verborgene Freund, 1819, written by a local, John George Hohman. This was later put into English as The Long Lost Friend. Its underlying principle was that “certain illnesses and afflictions were believed by the Pennsylvania Dutch to be evil in origin, from either a witch or the Devil himself, and a person so afflicted could not very well be cured by home remedies or medicine.” So to be a successful healer, or even a successful patient, one had to believe in both God and Satan. To the complaint of some people that the use of the Lord’s name in Brauching was blasphemous, he responded with the words of Psalm 50:15 “And call upon me in the day of trouble: I will deliver thee, and thou shalt glorify me.”

For the faith healers there was Der lange Verborgene Freund, 1819, written by a local, John George Hohman. This was later put into English as The Long Lost Friend. Its underlying principle was that “certain illnesses and afflictions were believed by the Pennsylvania Dutch to be evil in origin, from either a witch or the Devil himself, and a person so afflicted could not very well be cured by home remedies or medicine.” So to be a successful healer, or even a successful patient, one had to believe in both God and Satan. To the complaint of some people that the use of the Lord’s name in Brauching was blasphemous, he responded with the words of Psalm 50:15 “And call upon me in the day of trouble: I will deliver thee, and thou shalt glorify me.”

One highly regarded protection formula among them was the celebrated SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS, about whose origin they had some peculiar ideas: “The late Reverend Thomas Brendle, a foremost authority on folk medicine among the Pennsylvania Dutch, once stated that Hohman’s SATOR formula was traced to 200 BC in India.” A twelve-page Pennsylvania tract of the 1820s said “This is the song (first letter of each word used) sung by those three men, Shadrack, Mesack and Abednego, those that were allowed to be placed in the fiery furnace by King Nebuchadnezzar; then did God send [his] holy angel.” In fact, it is almost certainly a near-anagram of Pater Noster, 'Our Father', twice. I suppose that Protestants would believe almost anything except its Roman Catholic origin.

Also popular was the Himmelsbrief, a single leaf in German, but later translated and printed (in Pennsylvania) in English: “A Letter Written by God Himself, and Left Down at Magdeburg …” This protected one from all kinds of disasters, and so was often framed and hung on the wall; soldiers from the Dutch Country would carry them into war. Baptismal certificates would often be hung on the wall in perpetuity, to become eventually a reminder of one’s ancestors; sometimes, though, they would be buried with the individuals. They acted as passports to heaven by proving that they were baptised. --

- Gareth J. Medway.

No comments:

Post a Comment