This book is a work of folklore archaeology. In his preface Simon Young says that he is making an attempt “to recreate the boggart-lore of Victorian and Edwardian times.” Like all archaeological research this is done by excavating for fragments to put together a coherent picture of a particular culture at a particular place and time.

🔻

The material the author is digging through to recreate what he terms 'Boggartdom' is complex strata of oral traditions, rumour, news items, jokes, place names and dialect. The most basic questions he faces are, what is a boggart, where is Boggartdom, and when was the realm at its greatest extent and power? To do this Young makes use of a number of tools. One of the most important is the ability to digitally search through the texts of a great number of nineteenth and early twentieth century newspapers and other printed media.

As well as being able to search through hundreds of pages of print in minutes, this search facility allows the researcher to bypass the filters employed by folklorists and local historians in compiling their own accounts and records of boggart lore, and also to access boggart references in otherwise unrelated newspaper stories.

This facility is particularly useful in tracking the boundaries of Boggartdom through place-names, as many do not appear on maps or official records, and only came to light through accessing newspaper articles on unrelated subjects which referred to a boggart location in passing. For examples, the only references to Boggart Lanes in Leigh and in Mytholmroyd are from newspaper articles; on boys being prosecuted for playing pitch-and-toss in the former, and an attempted suicide in the latter.

As newspaper and official records are spread fairly evenly across the country, and not dependent on the location of folklorists and researchers (a problem very familiar to ufologists) the data gathered betrays much less of an editorial filter. In many cases this 'filter' is a function of social class, with boggart-related names being seen as of lower status.

This is also a problem with defining Boggartdom through research into dialect studies, and tracing the historical origins of the boggart through conventional folklore studies. Many writers seem to have made little distinction between terms such as 'bogey' and 'bogeyman' and 'boggart', seeing it simply as variant name for a child-scaring creature of parental warnings. Early printed references (the earliest in the Coverdale Bible of 1535) use the word to mean scarecrow, a usage which survived in some dialects. It is not until the Victorian era that Boggartdom begins to take on its clearest form.

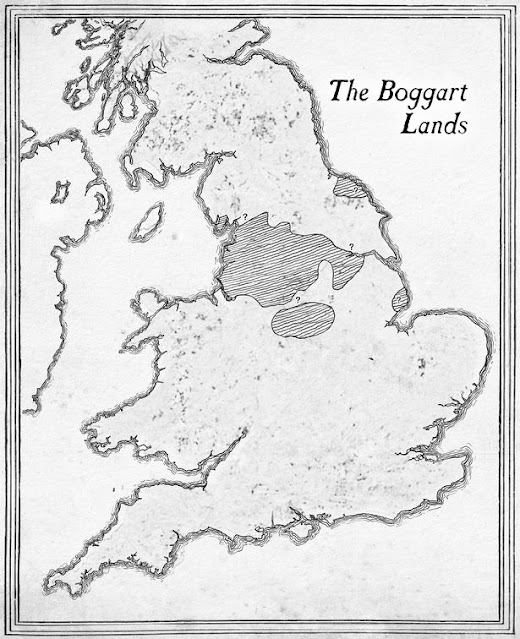

This is an area which is centred on Lancashire and parts of surrounding counties. Young, a Yorkshireman, refers to this reluctantly as 'Greater Lancashire', taking in much of the West Riding of Yorkshire, parts of the East Riding, Cheshire and possible outliers in the North Riding and Staffordshire. Generally in presenting these accounts the pre-1972 county boundaries are observed, which introduces the anomaly of Merseyside, where boggarts appear to be almost totally absent, perhaps because Liverpool received much of its folklore from Wales, Ireland and as an Atlantic port from even further afield.

The main source of contemporary first-hand boggart data for this survey, comes from the Boggart Census that the author conducted in 2019, after learning of an interview that a colleague had conducted with her father-in-law, which seemed to indicate that boggart beliefs were active well into the twentieth century. To find out how widespread they were, the author conducted a survey through various media outlets, including Radio Cumbria and Fortean Times. (Simon Young is the writer of FT's regular 'Fairies, Folklore and Forteana' column.) Response was slow until he decided, with some trepidation to use social media, but this eventually produced over a thousand accounts, many of which are summarised in this volume. The full texts of the census and the retrieved archive material are published on-line at https//doi/10.47788/QXUA4856.

The boggart, as recorded in print, rumour and first hand experience is a very vague sort of creature. It exists not only on the margins of daily life, but very much on the fringes of folklore scholarship. It is an 'unofficial' apparition, wary of being defined – or believed in - with any degree of clarity. It exists in a no-man's-land somewhere between 'respectable' supernaturalism – ghosts, polts, cryptids, UFOs – and the debatable areas of fiction, rumour, hoax, scary warnings for children and pub tales.

Young discusses the 'Social Boggart', which has similarities to figures like Springheel Jack. Rumours of a boggart haunting a location or building (usually an empty house) would often lead to crowds of people assembling. These would become mass social events, with fried-fish and hot-potato sellers doing a roaring trade, as well as local publicans. Sometimes these events would develop into boggart-hunts, where men armed with cudgels, swords and even firearms would chase supposed boggarts. This could end badly if, as sometimes happened, the reported boggart was actually a hoaxer in a sheet! Ghost-hoaxing was itself a significant phenomenon in the nineteenth century.

The heyday of boggart belief and activity was from the first half of the nineteenth-century, stretching, although somewhat attenuated, into the early years of the twentieth. Young's survey of Boggartdom in the press, and as reported from personal testimony in the Census, shows it falling away throughout the 1920s and 30s, scarcely surviving into the forties. Many of the reports from this era being in the form of reminiscences of an earlier period, or what parents have told the reporter as a child.

The varying boundaries of the boggart realm are shown in a series of maps, taking data from the Census and the literature search. The last remaining enclave of Boggartdom Young traces to Manchester, which he considers largely due to the existence of Boggart Hole Clough, a public park in the north of the city. There have been any number of 'Boggart Holes' and 'Boggart Cloughs' in Lancashire, but most of them have gradually been removed by urban development, or renamed in documents and maps. Apart from Boggart Hole Clough, the only other trace of Boggartdom I can find on Google maps are a cluster of roads in a suburb of Leeds. Perhaps it is socially significant that they appear to be part of a pre-war council estate, boggart names being too low-class for a private estate?

Boggart Hole Clough, however became a popular recreational spot in which to escape the smoke of Manchester; it was a popular sporting location and the site of political rallies. Its fame spread widely across the north of England, and beyond. Such an odd, but prominent name demanded some sort of explanation. This was often provided by children playing in the park creating their own tales of tribes of scary or mischievous creatures hiding in the undergrowth, which ensured the boggart remained a part of Manchester's consciousness.

The final section of the book examines the growth of the 'new boggart', which is largely a creation of writers, academics and folklorist. This seems to have been an attempt to fit the anarchic boggart of the urban and rural working-class of 'Greater Lancashire' into an academic schemata that included creatures of different natures from different cultures, perhaps attempting to do for folklore what Darwin did for biology.

Young traces this process from 1828, with the publication of the story 'The Pertinacious Cobold' in a volume of Lancashire folktales compiled by Thomas Crocker. The 'new boggart' became part of a family of supernatural creatures, along with brownies, fairies and household spirits, in what Young calls the 'goblinification' of the boggart. Boggarts soon became domesticated, in children's tales and fantasy literature, and were co-opted as a species of earth spirit by contemporary Pagans and New Agers.

In stories, plays, films and folklore collections they became remote from the anarchic and frightening creatures of lonely lanes, deserted houses and bleak moors that the ordinary people of the nineteenth century reported. These are the stories which Young has uncovered in searching digital archives of newspapers and other ephemera, allowing us a much clearer picture of the boggart as a creature of the folk, rather than the folklorist.

He concludes “the shift in methods of data collection and research may not matter for historians taking readings from the gilded barometer of high culture” but “the long closed door to the nineteenth century supernatural is gradually creaking ajar”

- John Rimmer

No comments:

Post a Comment