This is easily the most comprehensive and exhaustively researched book about foo-fighters. Randell makes the point that although ufologists were aware of such reports they did not make much effort to research them in any detail. He is particularly disappointed that prime witnesses were not tracked down and interviewed shortly after the war when their memories were still fresh, and since nearly all of them are now dead we are left to rely on old documents and reports.

🔻

Despite these shortcomings, Rendall has uncovered numerous sightings that occurred over Occupied Europe before November 1944 when the term foo-fighter was coined by American pilots. An RAF intelligence report ‘Phenomenon Connected With Enemy Night Tactics’ notes that one hundred occurrences of shapes or unidentified aircraft following bombers were recorded during 1940. In only one instance was a sighting confirmed by a fellow member of the crew, which led to the opinion that such reports of ‘shadowing’ was due to the strain of being on the look-out for enemy fighters leading to ‘the very natural tendency to think that any unidentified shape seen, or imagined in the sky, is an enemy aircraft.’

The possibility was also noted that the Germans might be experimenting with secret weapons under active service conditions, but it was puzzling that these things did not attack the bombers. Were they some form of tracking apparatus for German night fighters or anti-aircraft units? These were questions repeatedly asked and have never been adequately answered since.

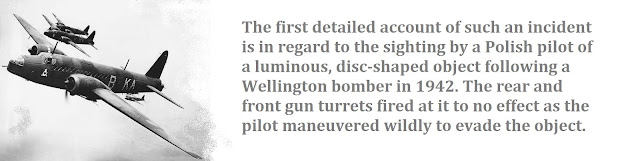

The first detailed account of such an incident is in regard to the sighting by a Polish pilot of a luminous, disc-shaped object following a Wellington bomber in 1942. The rear and front gun turrets fired at it to no effect as the pilot maneuvered wildly to evade the object. This was first reported in Flying Saucer Review (March/April 1962) so it is not a contemporary account. Researching deeper into it Rendall finds that the pilot’s name and rank is wrongly given in FSR (and subsequent retellings of the story); it is actually Sergeant Roman Konstanty Sobinski. No record of the sighting is to be found in the official records, but that might be because the report was lost or regarded as not worth recording in the first place.

There was a flurry of sightings by RAF crews in August 1942. Over Aachen a white light that came from the ground and flew on a level course for two minutes at an altitude of 8,000 feet was seen by four bomber crews. Over Osnabruck a ‘rocket’ was seen travelling horizontally at 15,000 feet leaving a white tail of light.

Many of these reports are of lights, or rocket-like objects. Bomber Command’s Operational Research Section (ORS) in March 1942 compiled data about 77 sightings that were regarded as aircraft fitted with a nose light. These lights were reported as white, red, yellow, green or blue and seen for a duration of from 5 minutes to 40 minutes and at distances of 100 to 1,000 yards. The odd thing is that Luftwaffe night fighters did not carry such lights, indeed they relied on being hidden by the darkness of night and would not want to indicate their position with a light. Another strange fact is that even at close range, gunners failed to identify an aircraft attached to the light and often did not even fire at it.

In July 1942 the ORS issued a report that dealt with sightings of ‘Chandelier Flares’. These consisted of an ‘invisible rocket’ that blasted from the ground and erupted into a 50 to 60 feet diameter ball of orange red fire that after a few seconds dripped fragments of light. Unlike normal anti-aircraft flak these flares did not generate much light or a shock wave. Furthermore, they were not aimed directly at Allied bombers. One theory was that they were possibly multiple flares dropped by parachute over bomber streams rather than being fired by a mortar or rocket from the ground.

Mysterious lights continued to follow RAF bombers including an instance where a Wellington bomber was followed by orange lights for 250 miles, from Le Treport to Saarbruken. The crew speculated that as many as five Junkers JU 88 bombers working in relay had been responsible, but why did they not attempt to shoot down their aircraft? And, why take so much effort and resources for seemingly pointless exercise?

From this initial selection of early reports the pattern was set for further sightings by the RAF and in 1944 by US air crews. Lights, rockets and jet aircraft were seen and even apparently shot down.

Rendall effectively rules out any type of German experimental or secret weapon for these sightings. As he notes crews frequently ‘saw’ Me163 Komet rocket aircraft and Me262 jet aircraft, yet the former never operated at night as it was more than a handful to fly in broad daylight, whilst Me262s were seen at night at times and/or locations where they were not operating.

The British gave these unidentified things a variety of names but the US nickname Foo-Fighter was the one that became an umbrella term for such phenomena, much like the term Flying Saucer a few years later. Like flying saucer sightings, foo-fighter sightings were reported in terms of witness expectations. Lights were enemy aircraft with lights fitted in the nose section, blasts of light and fire were rockets or jets.

Rendall eliminates the idea it was a man-made secret aircraft, such as the Horten Ho229 that had a swept wing design much like the objects seen by Kenneth Arnold in 1947. He is equally thorough about the possibility that very advanced saucer-shaped craft were built by the Nazi regime. Most of those craft were given publicity after the war. For example Renato Vesco in his book Intercept, But Don’t Shoot, written in 1956, describes a small Feuerball unmanned flying machine powered by a turbojet engine that could disrupt the radar and electronic systems of Allied aircraft. He also writes about a Kugelblitz circular aircraft that was an advancement of the Feuerball craft.

Rendall piece-by-piece demolishes Vesco’s claims as nonsense. He equally demolishes the post-war claims of self-proclaimed aeronautical engineers Rudolf Schriever, (Klaus) Habermohl, (Richard) Miethe and Professor Giuseppe Belluzzo (often misspelt as Bellonzo). They separately claimed to work on at least six separate flying saucer-like projects, and came out of the woodwork to say that flying saucer sightings are evidence that the US or the USSR have perfected their craft. Besides gaining publicity the object of these revelations was to get offers of work abroad and slyly promote neo-Nazi ideology. As Rendall notes the US Project Paperclip scooped up the most useful researchers and scientists and it is odd they were unaware of these projects that made Werner von Braun look like an amateur. Basically, that is because they are all full of fantastic claims with no substance to them.

The claim by Viktor Schauberger that he invented a flying saucer that used turbine blades to rocket it into the sky for the Nazis, is also debunked much in the manner of Kevin McClure’s article ‘The Schauberger Error’. See: http://magoniamagazine.blogspot.com/2014/01/the-schauberger-error.html

Pilots and witnesses have also come forward in the post-war period to report their wartime sightings. Again, these types of reports have to be approached with much caution. Many of them sound more like modern-day UFO encounter stories and over-time have become elaborated or the product of fantasy.

Rendall dismisses the possibility that foo-fighters were caused by optical illusions, hallucinations, combat fatigue, weather phenomenon, flak rockets, jets or rocket-propelled craft or saucer-type aircraft projects. He has no answer to what they are but he does think they fit Luis Elizondo's ‘five observables’ in regard to UAPs. Namely, the characteristics of anti-gravity lift, fast and sudden acceleration, hypersonic speed without leaving signatures, low observability and trans-medium travel.

The problem is that both Rendall and Elizondo think they are dealing with some type of literal craft and it is a shame this book does not go into the psychology or even sociological aspects of the foo-fighter phenomenon. Rendall does not mention the report by Jeffery Lindell who interviewed many US pilots, who concluded that:

‘A foo-fighter is a class of events, or rather, a collection of illusory sensations, which tends to mislead an airman, believing that a distant "light," either airborne or terrestrial, is another aircraft. It has been well proven that these instances of mistaking stationary ground lights, bright stars or planets gives the pilot of an aircraft conflicting sensory information which can lead to both visually and perceptually induced vertigo syndromes. Once a pilot has fallen under such a state, the light will seem to maneuver in a remarkable fashion, one that will defy all of the airman's attempts to "rationalize" the light's behavior.’ [1]

It would probably take another book to tackle those aspects of the foo-fighter phenomenon. Rendall certainly plays to the strength of his knowledge of aviation and gives us a thorough study of the technology of the period and why it was not responsible for these sightings. Like the UAPs of today they elude a definite answer.

- Nigel Watson

The book lacks a bibliography and index, but here is some useful further reading:

The Nazi UFO Mythos by Kevin McClure:

https://moremagonia.blogspot.com/2015/02/the-nazi-ufo-mythos-part-1.html

https://moremagonia.blogspot.com/2015/02/nazi-ufo-mythos-part-two.html

UFOs: The Nazi Connection by Nigel Watson

https://www.amazon.co.uk/UFOs-Connection-UneXplained-Rapid-Reads-ebook/dp/B01557MY24

No comments:

Post a Comment