Ronald H. Fritze, Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy, Reaktion Books, 2016.

Ronald H. Fritze, Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy, Reaktion Books, 2016.

"Egypt from ancient times to the present has remained a perennial object of fascination, fantasy, mystery and, at times, obsession and madness. The Egypt of one’s dreams is often just that, a dream rather than the real Egypt of history. That, however, to a large extent is what Egyptomania is all about."

🔽

So Ronald Fritze, professor of history at Alabama’s Athens State University, sums up the subject of his study, in which he aims to tell the story of that fascination from antiquity to the present day.

🔽

So Ronald Fritze, professor of history at Alabama’s Athens State University, sums up the subject of his study, in which he aims to tell the story of that fascination from antiquity to the present day.

The history takes up the book’s first, longer part, beginning with the ancient Hebrews. It’s debatable whether the treatment of Egypt in the Old Testament tales really qualifies as Egyptomania as such but, as Fritze points out, it was one of the two main sources of later conceptions – or misconceptions - about that civilisation. The other, presenting a more positive image of ‘an esoteric Egyptian civilization possessed of magical and occult secrets’, is the Hermetic texts, which became particularly influential in Renaissance Europe and created ‘a certain type of Egyptomania that exercised a powerful and enduring attraction for people already drawn to the occult and esoteric practices’.

Fritze goes on to detail the ideas about ancient Egypt that prevailed in the Greek and Roman eras, the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Enlightenment - an almost exclusively European story, although there’s a section on the medieval Islamic world’s concept of Egypt as ‘a land in which miracles occurred, magic was practised and lost treasures waited to be found’.

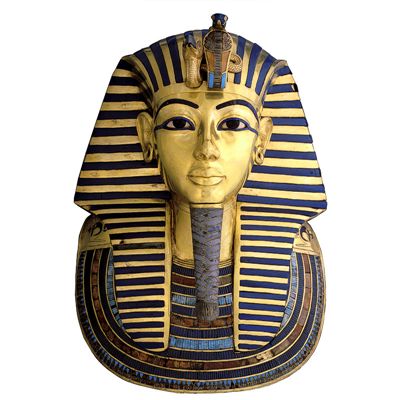

A pivotal event was Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798, which both opened that land up to hands-on historical scholarship and led to Egyptomania’s first manifestation as a mass cultural phenomenon, resulting in nineteenth-century ‘mummymania’ and the Egyptian revival in art and architecture. Fritze rounds off part one with an examination of the next surge of popular enthusiasm for things Egyptian, the ‘Tutmania’ that followed the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

While the book covers many areas of Magonian interest, the most directly relevant material is in its second part, ‘Varieties of Modern Egyptomania’. (The division between the two parts is somewhat arbitrary, with some overlap – and repetition – between them.)

The chapter ‘Occult Egyptomania’ examines the use of Egyptian themes and symbols by esoteric organisations such as Freemasonry, Theosophy and ‘Egyptianized Rosicrucian societies’ including the Golden Dawn and AMORC. It also looks at Edgar Cayce and his trance ‘readings’ about ancient Egypt, most famously concerning the putative Hall of Records. It’s a fairly comprehensive review of ancient Egypt’s place in Western esoteric traditions, but does have a significant omission in the absence of a discussion of Crowley’s Age of Horus.

In ‘Egyptomania on the Fringe of History’ Fritze sets out the history of alternative theories about the origins and nature of ancient Egypt, from the ‘pyramidology’ of the nineteenth century to subsequent ‘hyper-diffusionist’ theories of Egypt as the origin of all civilisation, and/or heir of a lost super-civilisation such as Atlantis, as well as those invoking ancient aliens. Naturally this includes the ‘Alternative Egyptology’ boom, centred on the writings of John Anthony West, Robert Bauval and Graham Hancock and hung on Cayce’s prophecies, in the lead-up to the Millennium.

Fritze devotes a particularly fascinating chapter to the one category of fringe theory that - presumably because the racial sensibilities involved mute criticism - has almost made it into the mainstream, even being on the curriculum in some US school districts. This is the ‘Nile Valley School’ of Afrocentrism which, borrowing heavily from hyper-diffusionist theories, maintains that the ancient Egypt civilisation was not only founded by black Africans but also, in its most extreme form, that it was the origin of all others, most significantly that of Greece. As a result, large sections of the African-American community now accept as fact that figures such as Ramesses the Great and even Cleopatra were black.

Unsurprisingly for someone in his academic position (especially whose previous books include Invented Knowledge: False History, Fake Science and Pseudo-Religions), Fritze is scathing about the ‘the morass of misinformation that constitutes the cultic milieu of alternative religions and fringe scholarship’. However, unlike many academic critics, Fritze has clearly studied the alternative literature in depth, and his criticisms of the excesses of the alternative camp are properly argued rather than airily dismissive - as well as hard to disagree with. (He’s surprisingly restrained, though, about Lynn Picknett’s and my The Stargate Conspiracy.) He also brings out the three-way symbiosis between the alternative theories, esoteric beliefs and fictional treatments of ancient Egypt.

Again unsurprisingly, Fritze’s own reading of history is unequivocally mainstream and conservative. So, for him, the Giza pyramids were tombs pure and simple, Cagliostro (who introduced Egyptian symbolism into Freemasonry in the eighteenth century) is ‘the great charlatan’ and ‘persuasive confidence man’, and the Hermetic books, while perhaps incorporating traces of ancient Egyptian religious thinking, were primarily inspired by Plato’s philosophy – all positions which have their challengers even within academia.

That said, Fritze succeeds admirably in his objective of telling the story of Egyptomania through the ages. It’s apparent that he is caught in the grip of that mania himself, and one senses a certain tension between his passion for the lore and magic of ancient Egypt and his historian’s persona. On the one hand he observes that Egyptomania is characterised by ‘false legends and misunderstood facts’ and often thrives on ignorance, writing that ‘interest often evolved into fascination, the lack of knowledge about ancient Egypt led to speculation, speculation led to fantasy’, but on the other he clearly enjoys that fantasy.

This is especially apparent when the fantasy is expressly presented as such and so can be enjoyed guilt-free: the chapters on Egyptian-themed fiction see Fritze in full-on fanboy mode, with detailed synopses and analyses of novels, short stories and movies. Although he declares that his survey isn’t comprehensive, it’s hard to imagine a more thorough job; he seems to have read every story ever written, and watched every TV series and movie ever made (Carry on Cleo included), that’s made even the vaguest use of an Egyptian theme.

Fritze’s enthusiasm is infectious, making Egyptomania an enjoyable read, laced with an often sardonic humour and full of fascinating and fun snippets, such as the serious consideration given, during the heyday of Tutmania, to naming the London Underground’s then new Northern Line extension, which passes through Tooting and Camden Town stations, the Tootandcamden Line. (Is it too late to reconsider? I feel a petition to Sadiq Khan coming on…)

Egyptomania displays an impressive command of not only the scholarly but also the popular and fringe literature – Fritze’s references take up nearly 50 of the book’s 450 pages - as well as the gargantuan amount of fiction. The result is both entertaining and informative.

- Clive Prince

No comments:

Post a Comment