I think it could be a good idea for people to start reading Merpeople at Chapter Three, and as a mental exercise going through it substituting for the word ‘mermaid’ the letters 'UFO'. Some readers might think that mermaids are entirely fictional and fantasy characters, and unlike other Fortean topics, could never have been considered as actual, physical creatures. This book shows just how wrong that idea is.

🔽

In fact they were taken very seriously indeed. In the eighteenth century The Royal Society published many reports of mermaids from sailors and scientists; and naturalists as distinguished as Carl Linnaeus were not slow to investigate the phenomena. Linnaeus wrote that the study of mermaids “could result in one of the biggest discoveries the Academy could possibly achieve”.

In a pre-echo of similar arguments about UFOs two centuries later, Royal Society member Peter Collison dismissed mermaid sceptics with familiar arguments, claiming that the sheer weight of observations by “navigators of credit” could not be rejected.

Descriptions of mermaid sightings by ‘trained observers’ were as clear and detailed as any close-encounter report with a nuts-and-bolts saucer, and naturalists investigating mermaid sightings used the techniques later included in every UFO investigators handbook, such as interviewing witnesses separately, and making sure that their stories were not contradictory. After all, what reason would solid citizens such as ship captains, priests, school masters and surgeons have to lie and create hoaxes? No more than police officers or airline pilots!

Of course in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries there was no photographic evidence to be argued over, but engravers and artists produced drawings and prints based on eyewitness descriptions, which could be, and were, debated at length. There was even a certain amount of ‘physical evidence’. A merman’s arm was retrieved from a ship off the coast of Brazil, and even whole bodies were presented for study. Some live specimens were claimed captured, but like alien saucer crash survivors they were mysteriously lost, hidden or proven to be hoaxes.

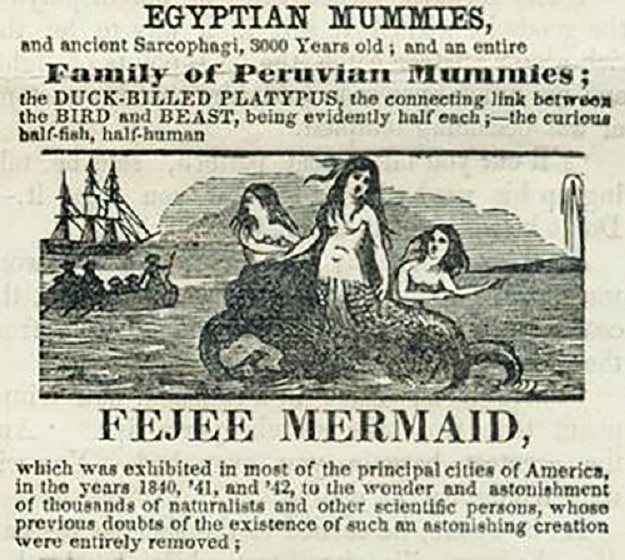

It was the recovered bodies that eventually led to the end of the era of scientific investigation of mermaids. In the nineteenth century, preserved specimens of a curious hybrid creature, looking like the upper half of a monkey and the rear half of a fish began to appear in Europe. Many of these came from skilled taxidermists in Japan. At first these were taken quite seriously, and even as late as 1845 a ‘mermaid’ specimen was subject of scientific interest in New York. But the death knell to serious ‘mermaidology’ came with P. T. Barnum’s ‘Feejee Mermaid’. Which of course was actually half monkey and half fish.

Visitors expecting to see the exotic figures depicted in the newspaper advertisements were rapidly disappointed and Barnum’s weird specimen became an object of ridicule, but still drew the curious crowds. Circus and sideshow promoters in Europe and America soon began producing their own mermaids for public display, including London’s Royal Aquarium, a venue for all sorts of curious and sensational sights and stunts, which exhibited a “Living Mermaid, half beautiful woman, half fish, submerged in a glass tank with live fish.” The fact that newspapers printed descriptions of how the exhibit was constructed did not put off the visitors.

But why mermaids, what was their origin? Scribner traces them back to the creation myths of the Babylonians, to supernatural figures like the fish-god Oannes from 5,000 BC, and the Assyrian fertility goddess Atargatis, who also symbolised the dangers of love and lust. It was this aspect of the female mer-person that interested the early Church Fathers who saw the mermaid as a symbolic representation of lust.

It was this adaption into Christian iconography that gave us the interpretation of mermaids as sexualised figures, with bare breasts, long hair, vainly admiring themselves in a mirror, demonstrating their seductiveness. These representations were shown in the decorations of churches and cathedrals, often remarkably sexualised, having two tails which they hold apart, with a strong resemblance to the sheela-na-gig carvings, exposing their genital area. The origin, of course, of the Starbuck’s trade-mark.

Early world maps showed mermaids, and to a lesser extent mermen - or ‘tritons - in the empty spaces of the great oceans. This was not simply decoration, as navigators fully expected to find such creatures in the oceans of the world, having being surrounded by such imagery in their daily lives. These figures in the margins of maps represented the exotic treasures and riches which European explorers expected to find in the farthest corners of the world.

Coming full circle, the mermaid of the twentieth century has recovered her original sexual power, but in a very different manner. Annette Kellerman, an Australian swimmer, was a movie star in America throughout the 1910s and 20s, and became a figure representing feminine strength and health, as well as beauty. She promoted swimming as a suitable exercise for women. The mermaid now became a symbol of healthy, outdoor living, but was soon co-opted into advertising, marketing and Hollywood, and ultimately recovering her position as a sex symbol, first given to her by the mediaeval Christian church!

This is a fascinating book, a true history of human 'vision and belief', with beautiful illustrations, many in colour, from a huge variety of sources. It is accessibly written with humour as well as scholarship, and with interesting material on every page. I have no hesitation in recommending this as my Fortean Book of the Year!

- John Rimmer

No comments:

Post a Comment